‘Analysis' means to pull something apart. In the NHS, this typically means understanding something – changes in unplanned admissions, for example – by breaking something down into simpler constituent elements.

But sometimes beliefs get pulled apart. Cherished assumptions; hopes for the future; things we need to be true. That kind of thing.

The Strategy Unit recently launched an online tool to support people planning local health and care services. Users can examine changes up to 2043.

Animated population pyramids allow people to see local demography change shape. Interactive charts allow them to explore how this might translate into demand for care across eleven different service types.

Professor Chris Whitty recommended this kind of planning in his 2023 Annual Report ‘Health in an Ageing Society'. Noting patterns in demography and geography, his first recommendation was that:

"The NHS, social care, central and local government must start planning more systematically on the basis of where the population will age in the future, rather than where demand was 10 years ago."

Whitty's report also points to a major uncertainty: will a 70 year old of the future be like the 70 year old of today? Will they be healthier? Unhealthier? Similar?

The experience of age need not match the number we give to it. The 60 year-old of 2024 is very different from the 60 year old of 1924. They might share a chronological age, but their experiences of living are very different.

Recognising this, Dr James Fries, Professor of Medicine at Stanford University, advanced the ‘compression of morbidity' hypothesis in the early 1980s. He argued that risk factors for non-communicable disease (cancer, heart disease, diabetes, etc) can be modified through lifestyle. Societies could therefore age and get healthier.

Fries' hypothesis conjures mental images of roller-skating Californians - baby boomers enjoying spinach smoothies and comparing data from their health apps. Few have ever believed that death could be beaten; but many came to think that it could come minus prolonged infirmity and suffering.

For a time, the evidence seemed to support this picture. Progress seemed real - perhaps even inevitable given the resources pouring into research and medicine.

Recent clouds have darkened this sunny picture. Humans, it seems, do not always benefit from energy-dense environments. Our food and transport systems, the way we work, the way we exercise, the way we use medicine. These and other factors have conspired to shake the assumption that morbidity will actually be compressed.

One such cloud came via a recent study from researchers at the UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies and University of Oxford. This showed that baby boomers were less healthy than previous generations at the same age. 50 year olds in 2025 have more chronic diseases than their predecessors. Is morbidity actually expanding?

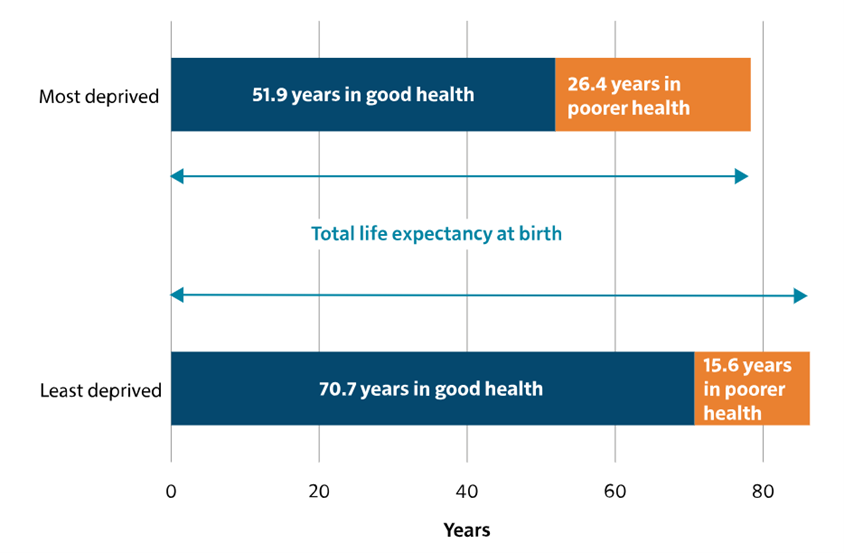

And, as the chart below – from Professor Whitty's report – shows, the consequences of expanded morbidity will be unevenly distributed:

Inequality in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at birth for females in the most and least deprived areas in England, 2018 to 2020

The jury is out. Ultimately, it is unlikely be one way or the other: roller-skating Californians will compress morbidity (their final jog ending at the morgue), while the less fortunate experience its elongation. Compression and expansion will coexist.

So, when it comes to NHS services, what should planners assume?

Our tool allows users to work this through for themselves. By varying assumptions – on fertility, on migration, on life expectancy – local planners can examine likely implications for A&E, elective and unplanned admissions (and more). They can do this at Local Authority and Integrated Care Board levels.

But we haven't left users to do this alone. Recognising the debate above, we used a panel of independent experts to generate assumptions about the compression of morbidity. What did they think? Can things only get better? Do people steeped in the evidence believe that today's 60 will be tomorrow's 50?

Our experts were, on balance, pessimistic. They thought that the older person of 2035 would spend longer in ill health than the older person of 2025.

And yet they were also uncertain. They saw an open future, amenable to improvement, with decline as a choice rather than a destiny.

The futurist Karl Schroeder said: ‘Foresight is not about predicting the future, it is about minimising surprise.'

High-quality choices need high-quality analysis. And high-quality analysis often means examining the assumptions it stands upon: even when these assumptions are both cherished and – on some level – wished for.

Our ability to minimise surprises of the nasty variety depends upon it.